Lucian Freud

- Cristina Bratu

- May 20, 2019

- 4 min read

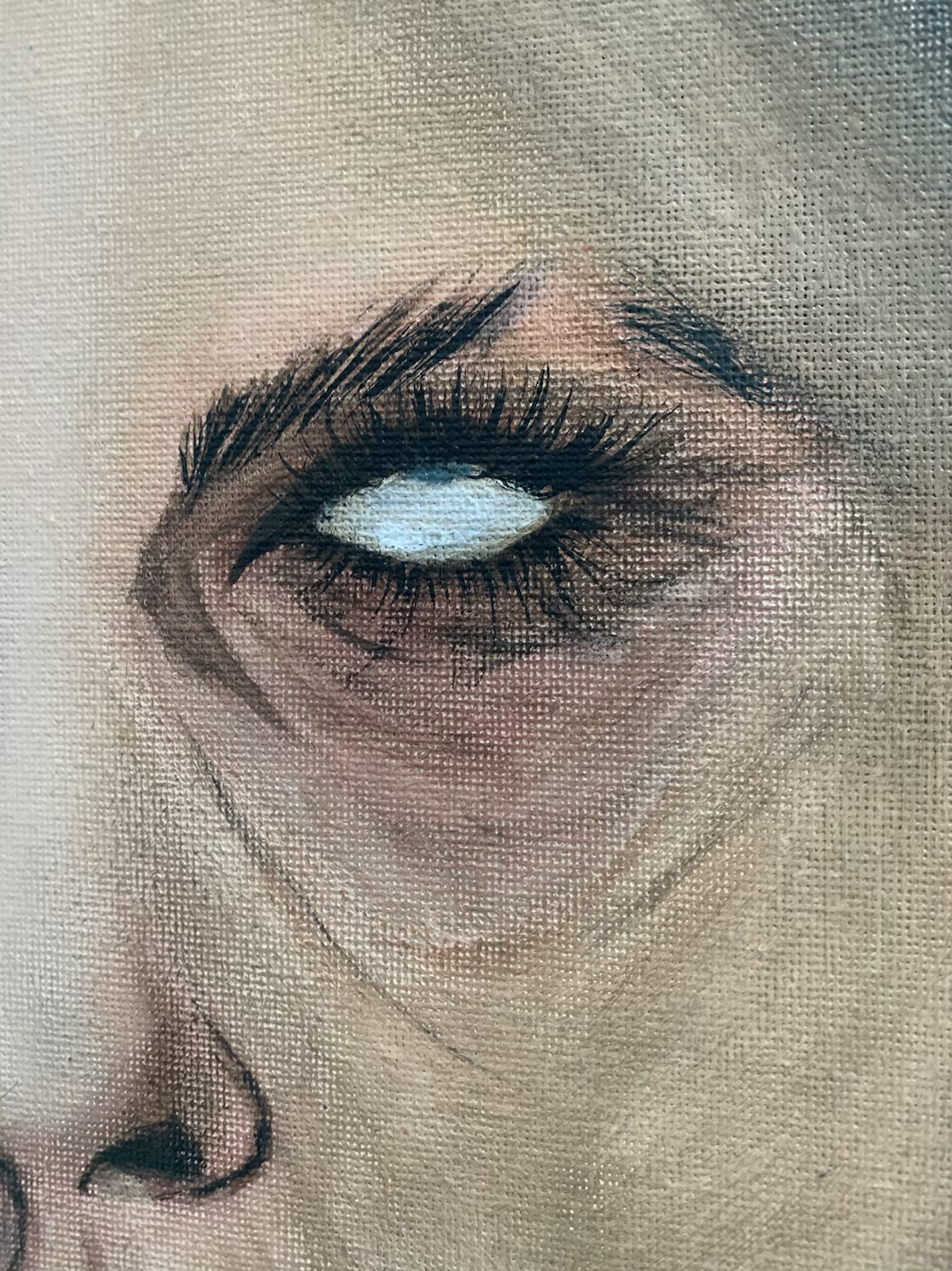

It must have been the dynamic qualities of skin—its susceptibility to time and its inevitable irregularities—that cemented Lucian Freud’s obsession. The focus of his tiny, 1978 Self-Portrait with Black Eye is the artist’s left eye, bruised and swollen shut from a fight with a cab driver. After the incident, Freud reportedly retreated straight to his studio so as not to miss the opportunity to capture the tender, fleeting blemish.This compulsion to render skin in its various states of vulnerability may have started decades earlier, with Freud’s 1950–51 portrait of his wife Kitty, titled Girl With a White Dog. In the painting, Kitty sits aloof on a couch, awash with soft window light, a dog on her lap. The work is a celebration of texture—the dog’s fur butts up against Kitty’s robe, the loose, striped couch cover folds and buckles—but the revelation of her right breast makes the painting Freud’s first nude, or semi-nude, and Kitty’s softly handled skin adds to the array of textures that surround her. As the artist reflected on the painting: “I was very attracted to the mole just above her breast. It stood out against the skin. I couldn’t take my eyes off it.”Freud’s fascination with skin and its endless textural transformations is at the center of “Monumental,” an exhibition currently on view at Acquavella Galleries through May 24th, which features a selection of the British artist’s nudes from 1990 to 2007. The two earliest paintings in the show are portraits of the performance artist and fashion designer Leigh Bowery, a staple of the London club scene and Freud’s longtime muse. Forty years after painting Girl With a White Dog, it’s apparent in these works how Freud’s fixation with his wife’s mole turned into a total sensitivity for the variegations of skin.

Bowery was known for his dramatic costumes and makeup, though none of that appears in Freud’s portraits. Leigh Bowery (Seated) from 1990 shows him nude, legs abreast, on a red chair in the artist’s studio. The paint itself is as thick as wet plaster, a scumbling technique indicative of Freud’s mature style. Bowery’s legs are pockmarked with a handful of small, rosy blemishes, and his imposing stomach is awash with fleshy rivulets. The canvas has a long, horizontal suture mark towards the bottom of the picture plane and a vertical one at its right; these suggest that Freud, amid his attempts to capture both the grandeur and intimacy of Bowery’s presence, adhered additional canvas to make the work larger. In Freud’s second portrait of Bowery, Naked Man, Back View (1991–92), the performance artist faces away from us, his imposing figure sitting up, broad and immovable as a boulder, his back a landscape of striation. To Bowery’s right is Freud’s studio wall; in lieu of a traditional palette, the artist mixed his paint on its surface. Here, it reads like a small Abstract Expressionis tpicture within the larger image, another moment of roughly hewn tactility that mirrors the worn skin of Bowery’s back.

Lucian Freud, Sleeping by the Lion Carpet, 1995–96. Courtesy of Acquavella Galleries.

Freud created his portraits slowly and deliberately; sitters were often required to be in the studio for hours at a time, multiple days a week, for months on end. He requested that the subject be present even if he was only painting the background. When Freud painted his 2001 portrait of Queen Elizabeth II—a small work measuring roughly 9 by 6 inches—he spent 38 hours with Her Majesty, spread out over 19 sittings. This is why so many of Freud’s subjects are shown lying down—so they could sleep while the artist painted.In 1993, Bowery introduced Freud to his friend Sue Tilley, who worked for the Department of Health and Social Security by day and moonlighted as the coat-check attendant of Bowery’s London club, Taboo. Tilley went on to become one of Freud’s most beloved sitters; the show includes four portraits of her, two paintings and two etchings. Tilley was a heavyset woman, a quality that was at the core of Freud’s desire to paint her. Her weight pushed the artist to further explore the interplays of depth and volume inherent to the figure. In Freud’s paintings, Tilley’s body unfurls in an almost baroque manner.

Another reason he returned to Tilley as his subject was her schedule: She often worked nights, and would consequently sleep in Freud’s studio during the day as he painted her. In Benefits Supervisor Sleeping (1995), Tilley is shown asleep on Freud’s studio couch: Her foot is tucked beneath a cushion, her hand cups her breast, and her sleeping face rests calmly against the couch’s arm. The reality of Tilley’s figure—the intricacies of her flesh, the folds of her skin softly colliding—are rendered with such reverence in these paintings that the architecture of her body reads like topography. “Skin is not inanimate,” Freud said. “It’s a living material.”The most recent work in the exhibition, Ria, Naked Portrait (2006–07), was completed over 18 months while Freud was in his mid-eighties. Despite his advanced age and failing health, the painting represented a new vision for the artist. Anomalous from the rest of the show, the subject’s face here is rendered in dabs of paint that stick out inches from the canvas; seen from the right angle, it dissolves from a portrait into a metropolis of protruding oils. Endlessly infatuated with his subjects, Freud followed his fixations toward discovery until the very end.

Comments