Cindy Sherman

- Cristina Bratu

- May 20, 2019

- 5 min read

"The still must tease with the promise of a story the viewer of it itches to be told."

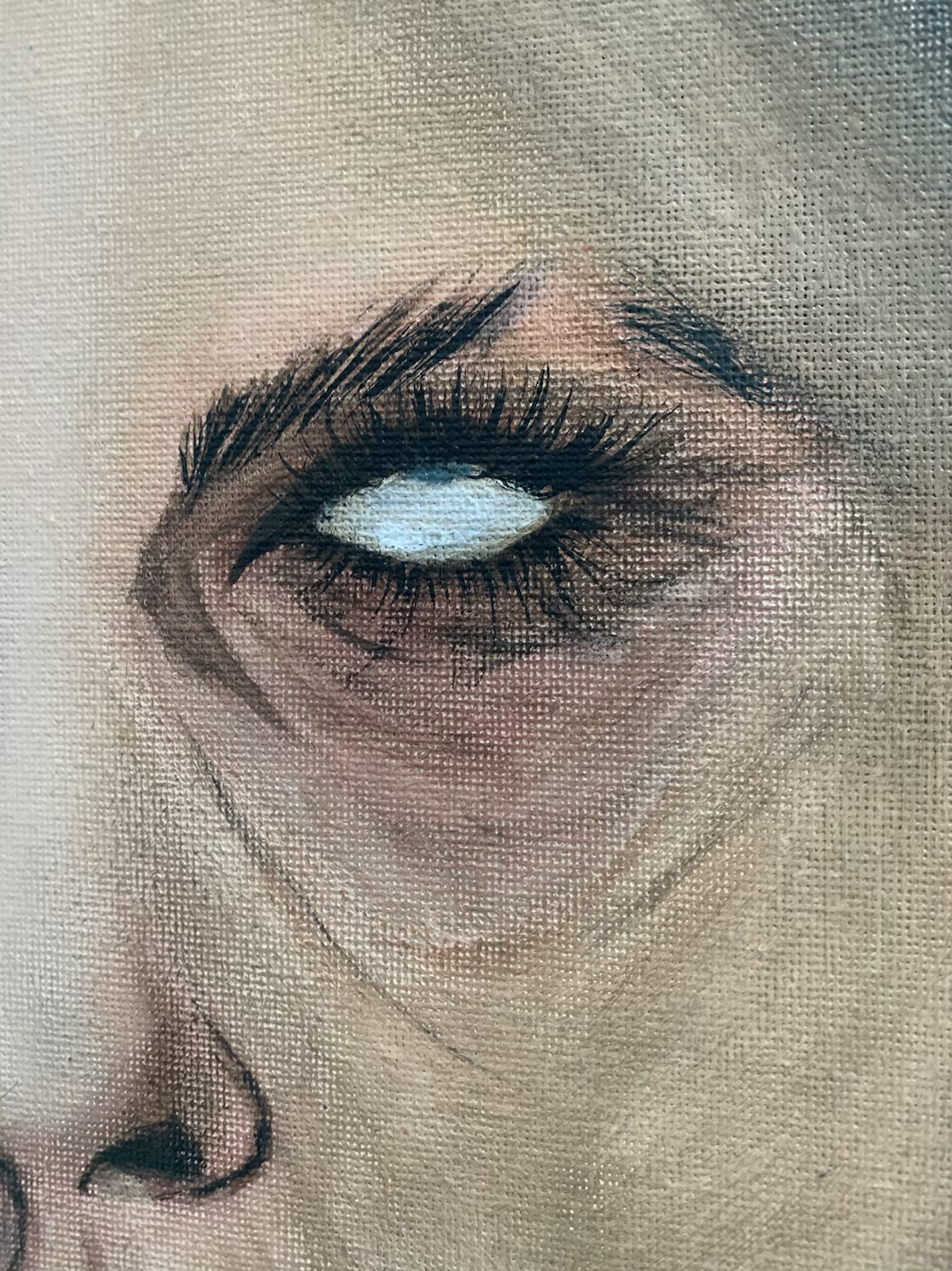

Cindy Sherman is a contemporary master of socially critical photography. She is a key figure of the "Pictures Generation," a loose circle of American artists who came to artistic maturity and critical recognition during the early 1980s, a period notable for the rapid and widespread proliferation of mass media imagery. At first painting in a super-realist style in art school during the aftermath of American Feminism, Sherman turned to photography toward the end of the 1970s in order to explore a wide range of common female social roles, or personas. Sherman sought to call into question the seductive and often oppressive influence of mass-media over our individual and collective identities. Turning the camera on herself in a game of extended role playing of fantasy Hollywood, fashion, mass advertising, and "girl-next-door" roles and poses, Sherman ultimately called her audience's attention to the powerful machinery and make-up that lay behind the countless images circulating in an incessantly public, "plugged in" culture. Sexual desire and domination, the fashioning of self identity as mass deception, these are among the unsettling subjects lying behind Sherman's extensive series of self-portraiture in various guises. Sherman's work is central in the era of intense consumerism and image proliferation at the close of the 20th century.

Recalling a long tradition of self-portraiture and theatrical role-playing in art, Sherman utilizes the camera and the various tools of the everyday cinema, such as makeup, costumes, and stage scenery, to recreate common illusions, or iconic "snapshots," that signify various concepts of public celebrity, self confidence, sexual adventure, entertainment, and other socially sanctioned, existential conditions. As though they constituted only a first premise, however, these images promptly begin to unravel in various ways that suggest how self identity is often an unstable compromise between social dictates and personal intention.Sherman's photographic portraiture is both intensely grounded in the present while it extends long traditions in art that force the audience to reconsider common stereotypes and cultural assumptions, among the latter political satire, caricature, the graphic novel, pulp fiction, stand-up comedy (some of her characters are indeed uncomfortably "funny"), and other socially critical disciplines.Sherman's many variations on the methods of self-portraiture share a single, notable feature: in the vast majority of her portraits she directly confronts the viewer's gaze, no less in the case of posed sex dolls, as though to suggest that an underlying penchant for deception is perhaps the only "value" that truly unites us.Long assumed to be a medium that "mirrors" reality with precision, photography in Sherman's hands simultaneously constructs and critiques its apparent subject. In this sense, Sherman's unique form of portrait photography functions, in part, as a sign for the subjective nature of all human intelligence and the unstable nature of visual perception.

Talking about her self-portraits, Cindy Sherman described how, as the youngest child and “total latecomer” in her family, she often dressed up to occupy herself, wondering, "If you don’t like me this way, how about you like me this way? Or maybe you like this version of me."

IMPORTANT ART BY CINDY SHERMAN

The below artworks are the most important by Cindy Sherman - that both overview the major creative periods, and highlight the greatest achievements by the artist.

Untitled Film Still #13 (1978)

Artwork description & Analysis: Untitled Film Still #13 issues from Sherman's epic "Untitled Film Still" series (they did not actually derive from a larger movie) of the late 1970s, by which she first made a widespread reputation for herself as a witty commentator on the female role models of her youth, as well as those of an earlier generation. In this example, Sherman employs her own image as to suggest the central character in a 1960s "coming of age" romance, the young female intellectual on the verge of discovering her "true womanhood," or the prototypical virgin. Maturing in the 1970s in the midst of the American Womens' Movement, later known as the rise of Feminism, Sherman and her generation learned to see through mass media cliches and appropriate them in a satirical and ironic manner that made viewers self conscious about how artificial and highly constructed "female portraiture" could prove on close inspection.

Some critics criticize Sherman's Film Stills for catering to the male gaze and perpetuating the objectification of women. Others, understand Sherman's approach as critically-ironic parody of female stereotypes. Others still, assert that both cases are simultaneously true, with Sherman knowingly taking on stereotypical female roles in order to question their pervasiveness. At the same time her adoption of these roles inevitably leads her to be objectified further.

Visual culture theorist Jui-Ch’i Liu asserts that many of these critiques focus on male spectatorship, whereas a reading of the images from the perspective of female viewers indicates the possibility of negotiating their own "desire and identification in relation to these images". Sherman has also implied that the works were created primarily for a female viewership, stating that "Even though I've never actively thought of my work as feminist or as a political statement, certainly everything in it was drawn from my observations as a woman in this culture. [...] That's certainly something I don’t think men would relate to".

Untitled Film Still #21 (1978)

Artwork description & Analysis: When the Museum of Modern Art announced in 1996 that it had just acquired Sherman's complete Untitled Film Still series, the curators knew they had laid claim to one of the most representative works of the early 1980s American movement of "appropriation," and "simulationism." Both terms refer to American artists' mimicking, in the first half of the 1980s, former art masterpieces or widely circulating images in the mass media, and critically reworking them to arouse a sense of unease in the viewer, indeed often suggesting that culture had become largely a game of theatrical posing and egoistic pretense. As Peter Galassi, then-curator of photography stated, "Sherman's singular talent and sensibility crystallized broadly held concerns in the culture as a whole, about the role of mass media in our lives, and about the ways in which we shape our personal identities. Here, Sherman takes on the role of the small-town girl just happening upon the Big City. She is, typically, at first suspicious of the metropolitan lights and shadows, only to be eventually seduced by its undeniable attractions.

Untitled #92, "Disasters and Fairy Tales" Series (1985)

Artwork description & Analysis: Part of the later Disasters and Fairy Tales series, this photo shows Sherman as a damsel in distress. Crouched on the ground, she fearfully looks away from the camera. With wetted hair and a tensed position, she appears as if she just walked off the set of a horror film. Sparse lighting centers the composition and lends an ominous tone to the entire photograph. Sherman successfully evokes one of the oldest, quasi-racist "cheap tricks" in the movie business, the setting up of a vulnerable female or private school girl (note the prototypical uniform of starched white shirt and plaid skirt) being preyed upon by some terrible, evil monster. The role goes back to Faye Ray's "scream queen" in King Kong, Judy Garland's Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz, and countless other popular culture favorites in everyday comic book series, graphic novels, Broadway musicals, and others media of the mid-20th century. By freezing the image into a kind of sorry, secular icon, Sherman demonstrates how art may act as a visual "truth serum," a force of social change by way of its ability to stop a viewer in his/her tracks and suggest how certain assumptions are culturally inherited, not necessarily "natural."

Comments